Fare Thee Well

Polonius: What do you read, my lord?

Hamlet: Words, words, words . . .

In the annals of You-Had-to-Be-There, my experience in Chicago, Ill. during the July 4th weekend of 2015 may top them all. It was as though I was transported out of time, body and space for a moment, shifting out of phase with the rest of life. In my pop-quantum physics understanding of the world, currently there is another version of me dancing to the strains of some powerfully evocative music on a stadium balcony with people from nearly every stage of my life. It is not an easy thing to achieve or replicate. How do they do it? In the annals of the Grateful Dead, once again, they proved to me that, “They aren’t the best at what they do, they’re the only ones who do what I do.”

As with shows, tours and experiences past, all hassles of planning, travel, social coordination, ticket fraud (yes, on the final night, one of our posse was told that his mail order was not valid!), work, all of it fades with the waning day. By July 5th, it seemed, all complications of sound, light and the chemical blend of musicians and audience had also melted away, leaving a band who could really play, or, in the parlance of loosey-goosey 1960s, a band who could really “get it on,” and get it on they did.

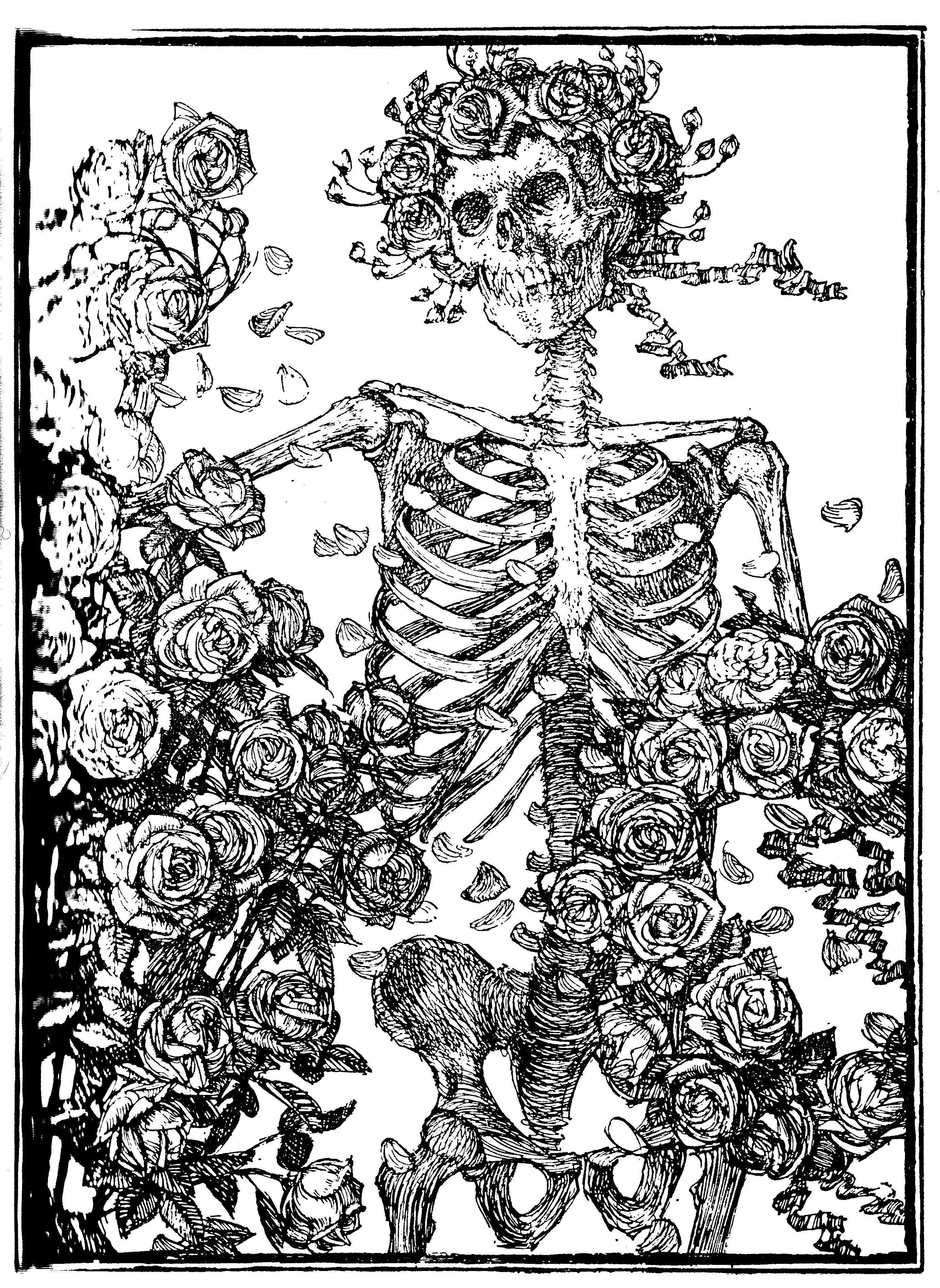

When the bright summer afternoon settles into evening, when the spotlights search the balconies for a deeper strain of humanity, when the energy coalesces around the pulsating stage, the thing that emerges is an indescribable animal of enormous proportions. The Grateful Dead is dragon mythology, an elusive creature at once sinewy and lithe all while being bloated and overindulged. It is a fire-breathing beast of fierce love. It is something which passes through the band-audience synergy and emerges separately. It is stepping out of the way to serve the muse.

As with any art form, there are missteps and stumbles and glitches. Even at their peak prowess, the Grateful Dead could gaff like no other. This, however, is what sets them apart. In continuing to strive, to search, there are going to be moments of failure. They are not abject failures, though Bob Weir did have me worried in the spring of 2013 when he took a tumble at the Capitol Theater in Port Chester. Phil Lesh has been known to hit a weak spot singing. Mickey Hart has, more than once, stepped out of pace with his counterpart Bill “The Drummer” Kreutzmann. All in all, though, the pieces eventually fall into place. In the thirty-three years I spent in seeing this band, I have had more missteps than the band members ever had while on stage. Nowadays we call them “epic fails,” and I have had more than a few.

When it all locked in, it was easy to forget who was who and playing what. I was dancing, enjoying the moment, cruising on the energy of the experience. That is why the 1950s’ and 60s’ performance art events were referred to as “Happenings,” experiences of the moment. The Acid Tests were Happenings, and this was the final installment in that journey. Garcia, McKernan, Kesey, Owsley, Ginsberg, Kerouac, Cassady, Mydland, Godchaux, and hundreds more contributors were not present, physically, but their presence could not be missed. The remaining artists piloted that bus furthur down the road for one last spin. It sure was an enjoyable ride. Thank you, all!

Phase 1: Santa Clara

As with many people who were excited for the Dead50 celebration in Chicago, mine came with full blown mail order and Ticketmaster anxieties. The amazing thing, is that that was back in January of 2015. It’s difficult to remember back that far, decorating envelopes, reconnecting with old friends, making plans for sleeping accommodations. As disappointment dawned on the many who were left without tickets, I felt blessed to have scored Chicago mail orders, something I had left to the hands of fate. Feeling sated with the coming events, I didn’t even bother trying to acquire tickets to Santa Clara. Then, a dear friend texted me.

“Wanna go to Santa Clara?” I was stunned. What to do? I had no idea how I could justify this to myself or to my family. What would this mean for the travel plans I had arranged? How could the credit card handle this? Was this too self-indulgent? As these thoughts coursed through my head, my significant other, Nancy, basically advised that I would regret not going. She was right.

Three days after our final school meetings, I was on board a plane to San Francisco. The layover in Chicago seemed apropos, while the flight over the halophile red of Owens Lake east of the Sierras seemed ominous.

The environmental news couldn’t help but signal the end of something, and yet I was traveling to California for a joyous occasion. It was all I could do to beat back thoughts of a pending apocalypse in the Golden State. In Palo Alto, then, how surreal was the cucumber water served in a carafe, even though I simply had ordered a Negro Modelo?

The environmental news couldn’t help but signal the end of something, and yet I was traveling to California for a joyous occasion. It was all I could do to beat back thoughts of a pending apocalypse in the Golden State. In Palo Alto, then, how surreal was the cucumber water served in a carafe, even though I simply had ordered a Negro Modelo?

Wandering around Palo Alto less than 12 hours after having left Maine still strikes me as nothing short of miraculous. This is the Space Age, indeed. I am a space traveler. Having left the lush and chilly coast where the lupine and other early summer flowers were just beginning to peak, I entered what appeared to be full blown or even late-summer. The paint peeling colonials and ramshackle trailers of Downeast were replaced with terracotta tiles and fancy coffee boutiques. Everything felt surreal and polished. As my travel companions Cori and Piotr each arrived in due time, we tried to find food, calm and comfort, even though we were giddy with shock.

There was a lot of quiet serendipity happening for me the entire time I was in California. Constantly in the back of my mind were the origins of the Grateful Dead and the development of digital media Silicon Valley. They seem to go hand in hand. Palo Alto, a hotbed of forward thinking, digital entrepreneurial spirit also happened to be the home of Ken Kesey’s electric venison stew dinners and the Chateau, a notorious crashpad of late-Beats and proto-hippies, including drop-ins Jerry Garcia and Phil Lesh. As if on cue during our second morning there, Piotr and I stumbled across the back alley which once housed Dana Morgan Music, the famed spot where Bob Weir first “accidentally” met Jerry Garcia.

While the entire Bay Area had been saturated in a swirling mix of the hi-tech revolution and psychedelic culture 50 years ago, the Grateful Dead inadvertently stumbled into a flashpoint role. I don’t mean flashpoint in any violent sense. Rather, they were at that bottleneck, the tight pinch of the hour glass, where 50s pop-Zen and Beat culture were squeezed through the tube of the Acid Tests. What emerged was writ large in Santa Clara 2015. Half a century after the Palo Alto and San Jose Tests, there we were, boogying in a giant football stadium tricked out with all your personal computing amenities. While there was no evidence of Kesey’s Thunder Machine, the stage set-up, multi-screen light show extravaganza and state of the art sound system seemed to be a culmination of this cultural intertwining and ever-evolving work. In a sense, this was the “Core Four” writing the last chapter in a career of Tests.

Music critics and picky Deadheads will find a lot to complain about over the course of those first two days of music. In fact, to many, the Santa Clara shows were being whispered about as dress rehearsals for the big event in Chicago. Nevertheless, there were plenty of highlights: just arriving, finding some of our ever-expanding circles friends, being handed a rose upon entry, soaking up the environment, hearing Trey Anastasio nail some of the early Grateful Dead material, the miraculous miracle of the rainbow ending set one, night one, all worth our efforts. The serendipity and synergy effects were in full force like lightning leaving traces of ozone in the air.

During my layover the day before in Chicago, I had watched the television screen with amazement as President Obama congratulated Jim Obergefell, the lead plaintiff in the 5-4 landmark Supreme Court decision on marriage equality. It was a uniquely American moment beyond expectation. This moment was tempered with the solemnity of the funeral for Rev. Clementa Pinckney, but it also resounded a note of hope for me. No matter what the forces of darkness throw at us, we shall overcome all obstacles. Just as Richard Blanco had written for Obama’s second inauguration:

“hope—a new constellation

waiting for us to map it,

waiting for us to name it—together.”

There we were at ORD, all types of people, watching these events together. Upon my arrival in the Bay Area, it took me a while to figure out the aggressively happy, toned dudes offering a cold beer to anyone and everyone passing them by on our CalTrain to Palo Alto. Could they be that excited about the Obergefell v. Hodges case? Is all of America celebrating I asked my fellow strap hanger? “No, man,” a dapper hipster in the seat next to me said, “It’s Pride weekend.” Oh, OK. And, then, toward the end of that first set on the first night of Santa Clara, a set which harkened back to the earliest days of the Grateful Dead (not one song penned post-1970 made it into the show), a rainbow appeared.

Had the crowd not been able to loosen up prior to this point, the rainbow certainly shook some cobwebs out. It was everything “beyond” that makes for a great Grateful Dead concert. How many times have I heard or read someone comment that this band controls the weather? The rain in Santa Fe in 1983? A cool breeze during a particularly spooky Black Peter on a hot day? Cloud to cloud lightning shows over a raging Saratoga or Merriweather or RFK? It is the type of unbelievable synchronicity that leads people to daydream that this aptly timed rainbow was manufactured, for what other explanation could there be? We, too, were overjoyed.

Sunday found us a little more familiar with the lay of the land in Santa Clara, though still wanting to find a vending lot. There was little to see in that regard. In the one grassy knoll we found, wandering without expectation, it was possible to run into old friends. I saw few. One auspicious run in was with Kevin, someone who I realized was present at my first show, Maine in 1982, and with me at my last, Oregon in 1995. It didn’t occur to me until Piotr and I had drifted our way back to Cori and the venue, leaving behind a purple glimmer of a Prankster eye or two in verdant space. Vestiges, vestiges.

Musically, I preferred night two of Santa Clara. Things had settled in for my crew. We had a better spot from which to enjoy the show–our own little balcony up in the “cheap” seats with a private bar, airport-style lounge and bathrooms, and it sounded great. We had our groove on much more, too, and the songs hit on some bouncier spaces of the 70s and 80s. Cori had been goofing on the lyrics to Hell in a Bucket all weekend, and when Bob Weir kicked it in, we were all smiles, dancing, bopping and spinning around. Yes! This is what we came for: the dance.

The second set of the second night was fantastic, if a little hollow in places. Like “thick air,” my understanding of “hollow” is difficult to express. Unlike Soldier Field, Levi’s Stadium seemed a little less than sold out. As a result, the sound had a chance to bounce around and find metallic rings and echoes, whereas a sold out stadium sound feels warmer to me, almost softened by the seamless crush of humanity. By the Half Step> Wharf Rat, though, I was so deeply immersed in the proceedings that I had arrived “there.” Time and space evaporated, and I was dropped into a slip stream of Grateful Dead that was beyond time and space. To quote Anastasio/Marshall, “I feel the feeling I forgot.” I was back in that enormous room, and they had facilitated this change.

The magnitude of being in a gargantuan stadium with 60,000 folks is difficult to explain. Much of what I was experiencing, energy-wise, was a bit off kilter. This was not the manic energy of a rambunctious, Northeastern crowd. Nor was it the surprise party energy that many a Colorado or Midwestern show once provided me. Is it because California now has legalized marijuana and a good portion of the audience is zoned out on all manner of edibles? Is it because this crowd still has monthly, if not weekly, shows by various surviving members of the Grateful Dead and other members of their of bands? No matter. We got what we came for, and we were able to give back what energy we could muster.

It is somehow fitting that my flight to Chicago the following day was graced by none other than Mickey Hart. Just about every member of the flight was tickled in some fashion. In the air, my seat neighbors, a delightful 60-something farming couple from Iowa, talked all manner of environmental concern. It was remarkable to be on the same page as someone in a conversation like this, let alone for four uninterrupted hours. How is that this form of dance, Mickey Hart’s menacing Beam and Billy Kreutzmann’s world beats, the deep tones of ethereal space and wonder of a searching Dark Star or mournful Wharf Rat, how is it that these things can bring us back to this one notion of caring? I have always felt it, the deepest tones of the universe, the core basic messages, the elements, the warp and woof that weaves us together.

Interim: Chicago Friends and Family

Landing in Chicago, it did not seem to strange to be making goofy hand gestures to Mickey Hart as he sat in his van waiting for luggage. Another goofball, he must have thought, as he offered me a fadeaway salute. Despite all the energy of the music in Santa Clara, the winding melodic threads and needlepoint stitching, it had been his segment with Bill Kreutzmann and Nigerian talking drum master Sikiru Adepoju which was still vibrating in my bones. Though Hart was his larger than life self 24 hours previous, we were now just two guys waiting for the next move in a busy July airport.

What a treat it is to have an old friend pick you up at an airport. Whisked away to a lovely Rogers Park home, some eleven miles north of Chicago’s downtown Loop, it was a far more pastoral scene than one would anticipate. Doug and I had a late night catching up, recapping my experience in California, hitting on all manner of topics with a tasty single malt, no less. Some delicious home cooking, days wandering the neighborhood and parks, Botanical Gardens, and the next thing I knew, we were eating dim sum in Chinatown on Thursday. It was time to drop me off at the Hilton for the Ripple Dead50 pre-show party and the gathering of my tribes.

I say tribes, because one thing that has become evident in middle age is the expansive nature of our social circles. When first starting out, we had our summer camp, grade school, high school and college friends to run into at shows. Now, some decades later for many of us, there are spouses, children, nieces, nephews, exes, new partners, and even online friends. Lynne’s Ripple Dead50 Facebook community sprang up in the wake of the mail order ticket panic as a way to help folks consolidate information and share a positive attitude. As we know, too many online communities center around kvetching and negativity. No so for Ripple Dead50.

Their party was a smash, even if I could not handle all of the factors coming together in my little pea brain. Maybe I had too much too fast. By the time my East Coast posse arrived, combining forces with people I know from all over the country and some slight excess, I felt like the images of our legendary musical heroes crawling around on a train through Canada. Rick Danko trying to slither out of the bar car in Festival Express just about sums up my experience. Just shy of 50, I have to keep reminding myself that I am not 25. Oh well, it’s the spirit that matters.

From the Hilton, we made our way back to Rogers Park to stay with one of Nancy’s oldest and best friends. We had siblings, children, nephews, friends dropping in for Mai Tais and barbecue, frisbee on the beach, hot beverages, cold beverages, access to the L, dogs, and a lot of history. I know of few contexts where all these layers of our lives overlap as seamlessly. The images which kept coming to me were like Venn diagrams of my life, layering and overlapping again and again. Of course, there were so many people involved, overall, that many of my older touring pals and I never crossed paths. Some of us bumped into each other, briefly, while being pulled in other directions, graciously.

In fact, all of Chicago felt this way to me. Other than the minor logistical flaws of the first show’s egress, too few doors open after the show and the crush of humanity trying to exit, everything was copacetic. Hotel staffs were patient. Police were polite. And no matter how crowded a hallway or aisle became, the audience was sympatico. Step on someone’s toe? Apologize. “Sorry, man.” 9 times out of 10, the response was something like, “No problem.” Or, “It’s all good.” Or, “Pass on through, bro.” The city demonstrated just how to absorb and Tai Chi walk 100,000+ refer mad Dead Freaks in and out without a hitch.

Chicago is no stranger to festivals, either. There is always some block party spilling over into a music festival or large scale food event on any given weekend in the summer. The Museum Campus and Grant Park can absorb a lot of people. Traffic flows on Michigan Avenue, albeit slowly, but it flows. One of the more remarkable facts of this weekend, in this vein, is just how many pre- and after-parties raged from Wednesday through the wee hours of Monday. It was a giant event, and for the life of me, I cannot think of another city as prepared to take it all on as Chicago.

Late-Sunday through early-Monday morning, my gang could not tear ourselves away from the window at the Congress Hotel. With the Buckingham Fountain and flower gardens all lit up and the last vestiges of concert stragglers still spinning along Michigan Avenue, we never wanted to see an end to the greatest show on earth. There was yet more to see and do and we felt the pull despite the prescribed 7 am departure. We had hoofed the pavement hard but never regretted one city block of it–up to meet friends at the Big Bar in the Hyatt, strolling the River Walk on the once “Bubbly Creek,” admiring the architecture of Second City, home to the steel buttressed skyscraper. Well done, Windy City.

Phinal Phase: Soldier Field

Doug, my brilliant, frank host for the interim phase between Levi’s Stadium and Soldier Field, expressed how brave and bad ass the Grateful Dead organization was to host their Fare Thee Well concerts in the venue where Jerry Garcia made his last stand in 1995. That had been a tour of major disappointments and disasters, and we needn’t revisit that, here. However, his point is well taken. Of all the places in this country they could have chosen, there is something about this choice which suggests getting back on the horse.

Musically, I had left expectations behind long before arrival. This was to be a weekend which exceeded all that. However, there was always a hint of anxiety. What if the proverbial air was sucked out of the room? What if the gaffs outweighed the triumphs? What if the picky Deadheads, already cranky about the choice of Trey Anastasio on lead guitar and vocals, really did not like him one bit? Having been a fan of Trey and Phish since 1987, I was worried for him, not because I didn’t think he could meet my expectations. Rather, I was worried that his reputation would be forever marred by disappointing hundreds of thousands of jam-hungry fans.

I use the word “jam” offhandedly, too. In modern parlance, we now have a subgenre of rock known as the “jam band,” an atrociously cheesy title, in my opinion. If anything is going to make an urban hipster or music aficionado of any stripe sneer at a summer festival, leave it to the word “jam.” Another misguided notion is the expectation that everything must be some sort of improvisational soup spinning off aimlessly from a structured point of departure. When it comes to the music of the Grateful Dead, nothing could be further from the truth. Grateful Dead improvisation was always compelling because the structured melodies and strains of songs always lurked just below the surface of said improvisation. The more familiar one became with the music, the more assiduously one’s attention to the details could become. Changes were anticipated, and then delivered upon. When things did go off the rails into “free flight,” there could be a near audible gasp of recognition.

Phish is another story. Those four music nerds are capable of stepping off the curb of a song to a point of seemingly no return at a moment’s notice. In the 1990s, they could wander for up to 40 minutes at a time, far from anything recognizable, holding down a backbeat all the while. In the context of the Grateful Dead 50 celebration, fans wondered more about whether Trey would “nail” the structured parts required of the song catalog. In order for Terrapin Station to properly crescendo, for example, one must hit the parts Garcia carefully composed. The tension of a song like The Music Never Stopped depends on the audience anticipating the flip from spacey jazz wandering to foot stomping romp on the main melody.

Well, from the moment they shot out of the gate with Box of Rain, I could sense a different power and intentionality than had been evident in Santa Clara. Phil began the proceedings with Box of Rain, the last song the Grateful Dead had played in Soldier Field in 1995: talk about hopping back on the horse. From there on out, I knew that these were going to be intentional and considered and meaningful shows. Trey had a lot of pressure on him, and he was delivering the structure with a little extra sauce. Holding the intensity and pressure of the music together in a gigantic stadium is no easy feat as the sound wanders off into the stratosphere. The compression of an enclosed space is lost, and there are plenty of ways to be distracted.

I can’t say that I saw many “intense” stadium shows back in the Grateful Dead’s heyday. These four come to mind: JFK in Philadelphia, 07/07/89; Cardinal Stadium in Louisville, 07/06/90; RFK in D.C., 07/12/90; Rich Stadium in Buffalo, 07/16/90. I had tried before, and I tried again, but the stadium vibe never really caught fire like the little coliseums and hockey arenas dotting the landscape east of the Mississippi. My experiences in the summer “sheds” like Deer Creek and Alpine Valley were far more successful. So, for these guys, the Core Four originals with three hired guns, to pull off a coherent, powerful, emotive and cathartic tribute to the music which has meant so much to so many for so long in a gigantic football stadium is remarkable.

Musically, the fact that the old was sprinkled in with the new brought the necessary gravitas to the experience. Phil Lesh, for one, never held back from reaching into the depths of the Grateful Dead’s murkiest psychedelic corners of the catalog. What’s Become of the Baby, Mason’s Children, New Potato Caboose, Golden Road and Mountains of the Moon all harken back to an alternative, neo-Victorian, Art Nouveau, Bay Area, late-60s life that is now mythical and ethereal, a life whose remnants are quickly evaporating. Lesh coaxes the last vapors of a time engulfed in self discovery and mystery, a darker corner of the 1960s feared by many and rarely explored as deeply as it had been by those who stood before us now. Peppering those touchstones among the more raucous and familiar “newer tunes” evoked a depth and weight achieved and articulated by a relative few hearty souls.

Like the fireworks that graced the show’s climax on July 4th, and the surplus which emphasized the setbreak on July 5th, this was a band who lit a community fuse. They brought us together, and together, we all made the music, filling in gaps where need be in our own heads. We danced as if in an embrace, swaying to a melody of our own American imagination. It is a dance of possibility despite the technical limitations. It was a big parentheses around an era, though such punctuation is always followed by an ellipses of fading time. Best of all, as Bob Weir led everyone through an eerie rendition of Attics of My Life, the final song, accompanied by a slide show of band members past and present, I decided right then and there that it was a tasteful tribute. There was no hyperbole. Never once did a cheese ball utter anything close to the rock cliché, “Hey Chicago, do you feel alright?” It was simply time to let the words speak for themselves, hug and take a bow.

In the secret space of dreams

Where I dreaming lay amazed

When the secrets all are told

And the petals all unfold

When there was no dream of mine

You dreamed of me

(Hunter/Garcia)