This post first appeared on the Phish.net Forum on September 6, 2017.

OK, so here's a weird bit of Midcoaster perspective on what it meant / felt like to be a Deadhead in the 80s. This perspective has faded a bit in emotion and sense since this is something that is generally on the wane. Take it with a rock of molecule.

In the late-60s and early-70s, many hippies and freaks who had been devoted to Civil Rights and the Anti-War movement, said, "f*** it." They blended pages from Ken Kesey's and Helen and Scott Nearing's play books. At a massive Berkeley Free Speech rally from 1964, Kesey showed up with the Pranksters and the Hell's Angels. He stepped up to the mic in front of dreamy antiwar believers and said, "Do you want to know how to stop the war? Just turn your backs and say, 'f*** it.' " People were pissed and shocked, for that moment.Much earlier, in the 1930s, Helen and Scott Nearing had dropped out of the Wall St. and Madison Avenue world to live "the Good Life" as they called it, subsistence farming in Maine. They were done with corporate greed and the shallow trappings of cultural materialism. To them, running a rustic farm on the shores of Penobscot Bay seemed a better option than harvesting riches for their own interests. They might face lean times, but it'd be better than demoralizing their own sense of conscience.

Once the idealists of the 60s faced the brutality that was 1968 and the shock of Nixon's 1970 invasion of Cambodia, many simply blended those two playbooks (Kesey and Nearing) and moved to rural New England. It was a hearty bunch who settled Maine where land was cheap. Hippies faced many challenges with locals, but New England's old fashioned brand of conservatism ("Do what you want on your land, just don't mess with my land") boded well for them. Those who could manage to split their own firewood, grow food, hunt, fish, work hard and do anything to survive soon found themselves a new thread of the fabric in their local communities. Still others hightailed it out.

|

| Baron Wormser's memoir does a great job describing the 70s Maine homestead experience. |

Mainers called these hippies "back-to-the-landers," and by the late-70s, the very life of rural Maine was transformed. The underground Head economy (see Jarnow's Heads) helped supplement wants and needs. The weed economy took root in earnest, bolstered by vast amounts of unorganized territories in Maine's north and Downeast woods. Coops and trading posts popped up, here and there. Gatherings like the Common Ground Fair were established to share agricultural dos and don'ts. Organic farming also became a real part of the economy.

|

| This culture is now woven into the fabric of Midcoast Maine. |

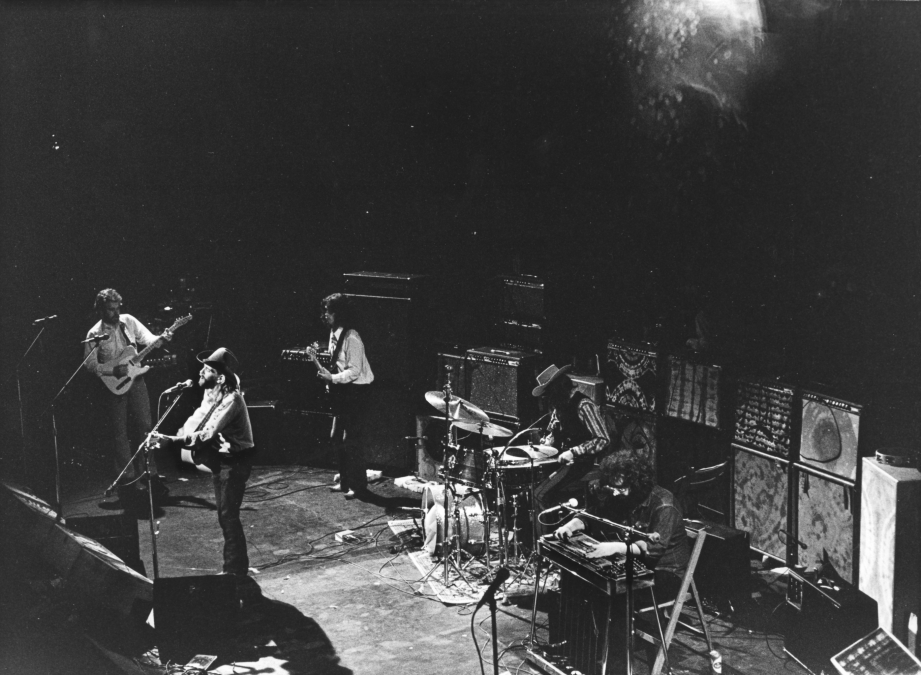

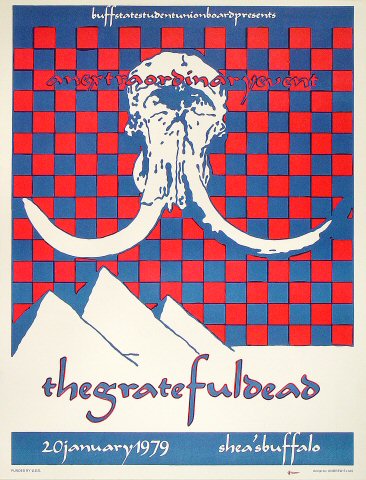

While the local music scene took off in the form of bluegrass and various forms of hippie country (hey, unamplified music only costs as much as the instruments and the sweat equity, right?), there wasn't much in the way of a national hippie act circuit in Maine. Sure, the Grateful Dead played in the Bangor Auditorium in 1971, but that was more a fluke of the times. It wouldn't be until 1979 when the "People's Band" returned to the Great State of Maine. When they returned, though, they returned en force.

In the spring of 1979, the Grateful Dead snuck back into Maine for the first time in May (5/13/79). This was a different move than the usual college circuits that the Dead repeatedly hit in the 1970s. Maine was a bit of a "hinterland," and the Heads liked it that way. It was a cheap place to live and get down to some dirty overall business. Was it Rick Turner of Alembic (a guy with deep Maine roots) who may have nudged the promoters this way? Was the call coming from Maine? Either way, the People's Band was hitting the scene, and reports were positive. This was an old high school girlfriend's first show, and she recalls walking up to the box office with her older brother a few hours prior to show time and buying a ticket.

The Dead returned to Maine the following September (9/2/79), pushing a little further up the road to Augusta. By all accounts, this was a super relaxed and super psychedelic environment. It was what people used to call a "family" night, or a show that was just for the Heads. If you don't know what that means, try to picture a venue full of "freaks only." On those nights, the electricity may be palpable, but it's so scrambled that it's a lazy lightning. Everyone has plenty of room to move. Dancing wildly, no one even so much as touches each other.

|

| Lucky duck ©Jay Blakesberg documented 9/6/80 in all it's glory! |

These travel routes or rituals seemed to become routine quickly. The Grateful Dead organization either realized they were tapping into a heady market, or the heady market was interested in re-tapping into their motherlode of energy. Either way, Maine became a regular stop at this point (almost as far as one can be from San Rafael and still be in the U.S.). There was a groovy scene already here, and it was sympatico. May 1980 saw the Dead make another stop in Portland (5/11/80), cementing the sense of routine. And, according to my sources, Maine shows simply had that reputation of being "for the faithful."

These early-80s vibes are difficult to explain. A show "for the faithful" back then often meant that alcohol was a sort of ancillary side show, mostly something to calm wiggy energies and help people cool off at the end of the day and sleep. Lysergic energy coursed through the scene, and as kids, we had a strong sense of history, that the "Heads" were present. By Heads, we meant people who were 60s dropouts, back-to-the-landers, Vietnam Vets, Carter-pardoned draft dodgers, old school outlaws and dope smugglers, bikers, as in real bikers, hardcore Heads who'd been to the Fillmore East, Winterland and Woodstock, traveling gypsies who'd been living alternative lives for what then seemed like a long, long time. They were older people who were serious about this lifestyle. It wasn't just a party to blow off steam in order to put in another 6 months at the bank. It felt like a way of life.

|

| Note triangular stage canopy, signature Lewiston; ©Jay Blakesberg. |

To set the record straight, I did not have the opportunity to see the Grateful Dead until 1982. However, these stories were alive and around me back then via siblings, cousins and older friends, which is why I feel it's important to set that little bit of a stage for 9/6/80. Read the reviews on archives. There are great stories in there. They convey some of the feeling. What has been handed down to me is something that has always seemed a bit of a dream, a bit of that "sunshining daydream" that seemed to wane all too quickly as my understanding dawned.

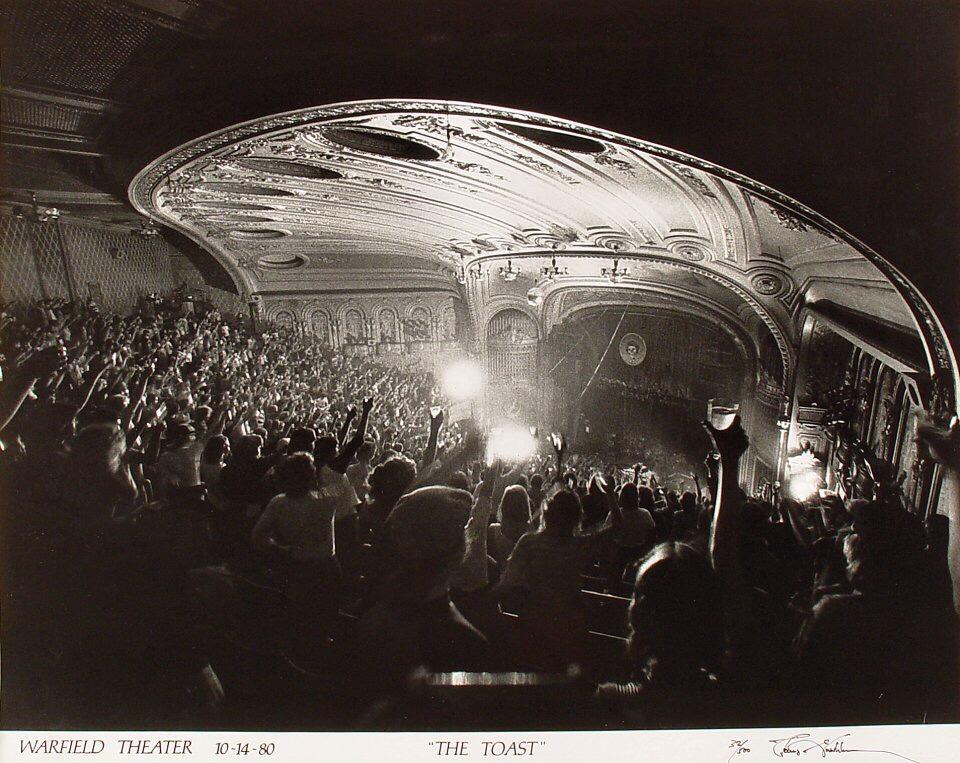

For many who have recounted the day to me, the decision to go to Lewiston was a whim. "Oh, sure, there's one more show on this tour. I can make it." For others, it was a chance to come out of the woods, fields and back 40s of Maine to celebrate another summer. The electricity flowed. Levon Helm played. At some point in the afternoon, there was a transition to the Dead. The music seeped in gradually. The dancing picked up in earnest. It was a flat fairgrounds on grass. There was no security. In short, in the middle of Lewiston, Maine, in 1980, the fortunate attendees were treated with a taste of something akin to a Veneta Field Trip.

|

| ©Jay Blakesberg |

In that special "family night vibe," in the empty spaces between notes, one hears ankle bells, the squishing of dancing feet in grass, one's own breathing. Somewhere deep into the nearly two-hour first set, it would be easy to imagine a slight panic-feeling, Wait, is this the second set? Are they only doing a one set show? It is a hot, but not too hot, summer, but not summer, Labor Day feeling, and the world is melting again. The music which started so calmly is building to wild crescendos. The music is absolutely perfect. Everywhere there are familiar faces, knowing smiles, but names elude, and we seek the open spaces. Nowhere "inside" this venue is it crowded (except for those "bug-eyed" people down front).

It's a very difficult thing to convey, but those years always carried a sense of history. During the early-1980s, I was astonished that the culture still existed as it did, and boy did it exist! One could fully hop on the bus, and one felt that it was not child's play. Yes, you could join the circus and run away, but it was a serious circus, more like a bent carnival.

Crank it up, and maybe, just maybe, do it in a yard to feel the grass under your feet with a headfull, plenty of space to freak freely. Maybe, just maybe, a little bit of that magic will come through the airwaves.

For further reading, check out Jesse Jarnow's book Heads.